Does the Twin Transition Co-Evolve with Inequality?

8 December 2025

The twin transition is reshaping Europe’s labour markets, yet its social implications remain insufficiently understood.

Our latest report on the impact of digital and green transformations on income inequality and employment quality shows that Europe is entering this transition from an uneven starting point (please see report "The impact of twin transition on income inequality and employment quality" https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17630637).

Rather than producing immediate convergence, the evidence suggests that existing divides often condition, and in some cases reinforce, the way benefits and opportunities are distributed.

A first element that emerges from the analysis is the persistence of income inequality across Europe. Despite major economic shocks and successive waves of policy intervention, the relative position of countries has changed very little over the past decade. More unequal economies remain at the top of the distribution, and the most egalitarian ones continue to occupy the lower end. These differences are structural rather than cyclical, rooted in national institutions, labour-market organisation, and industrial specialisation. The transition to a greener and more digital economy has not altered these patterns so far.

The geography of transition-related employment reinforces these asymmetries. Digital jobs have expanded steadily, but largely in countries already characterised by stronger skill bases and more equal income structures. Green employment, by contrast, is more prevalent in economies that display higher inequality and depend more on agriculture, construction, or energy-intensive activities. Meanwhile, occupations that combine both digital and green competences remain a very small and slowly growing share of total employment. This limited overlap indicates that the twin transition, as it stands today, advances along parallel rather than integrated trajectories.

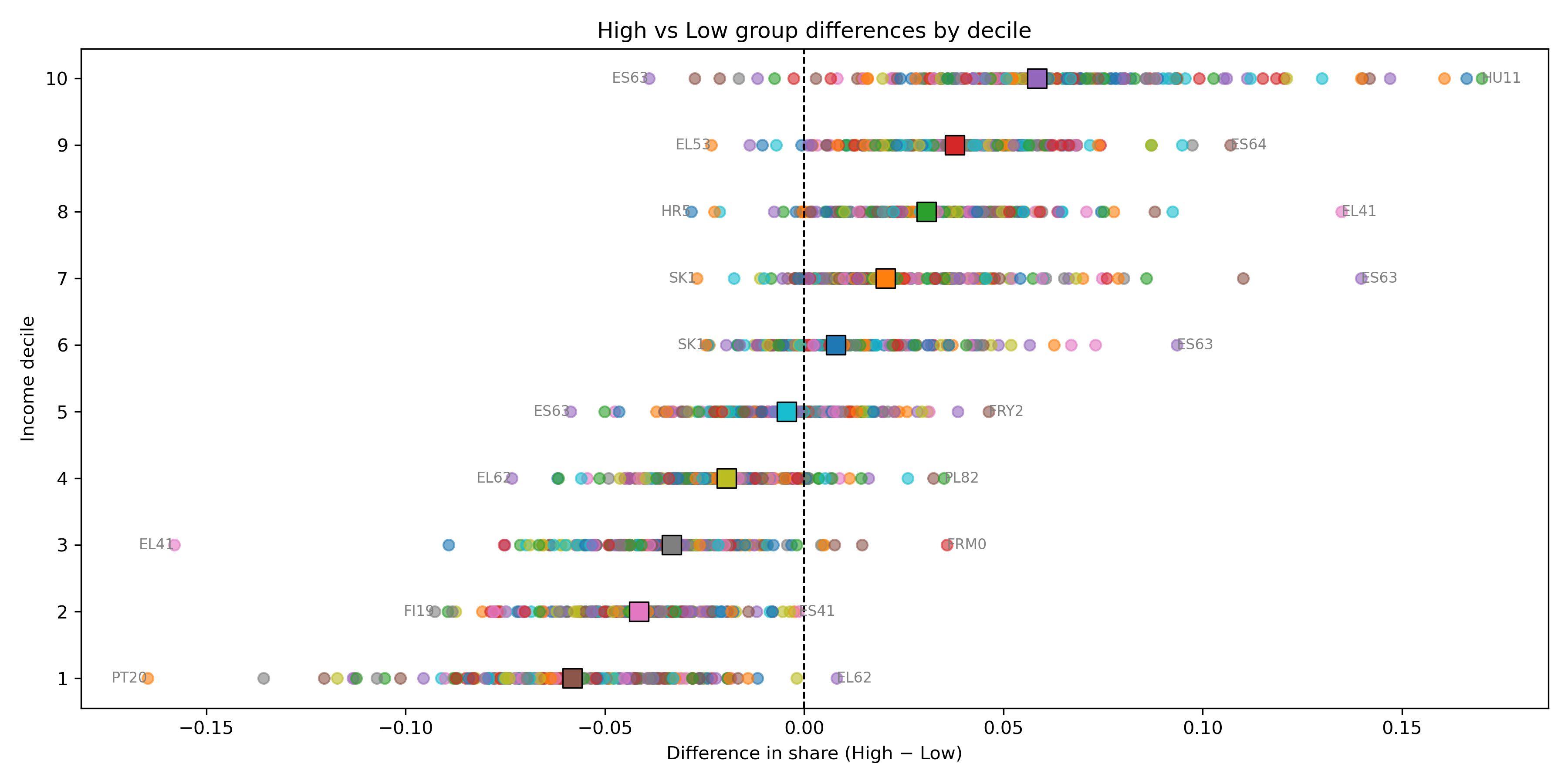

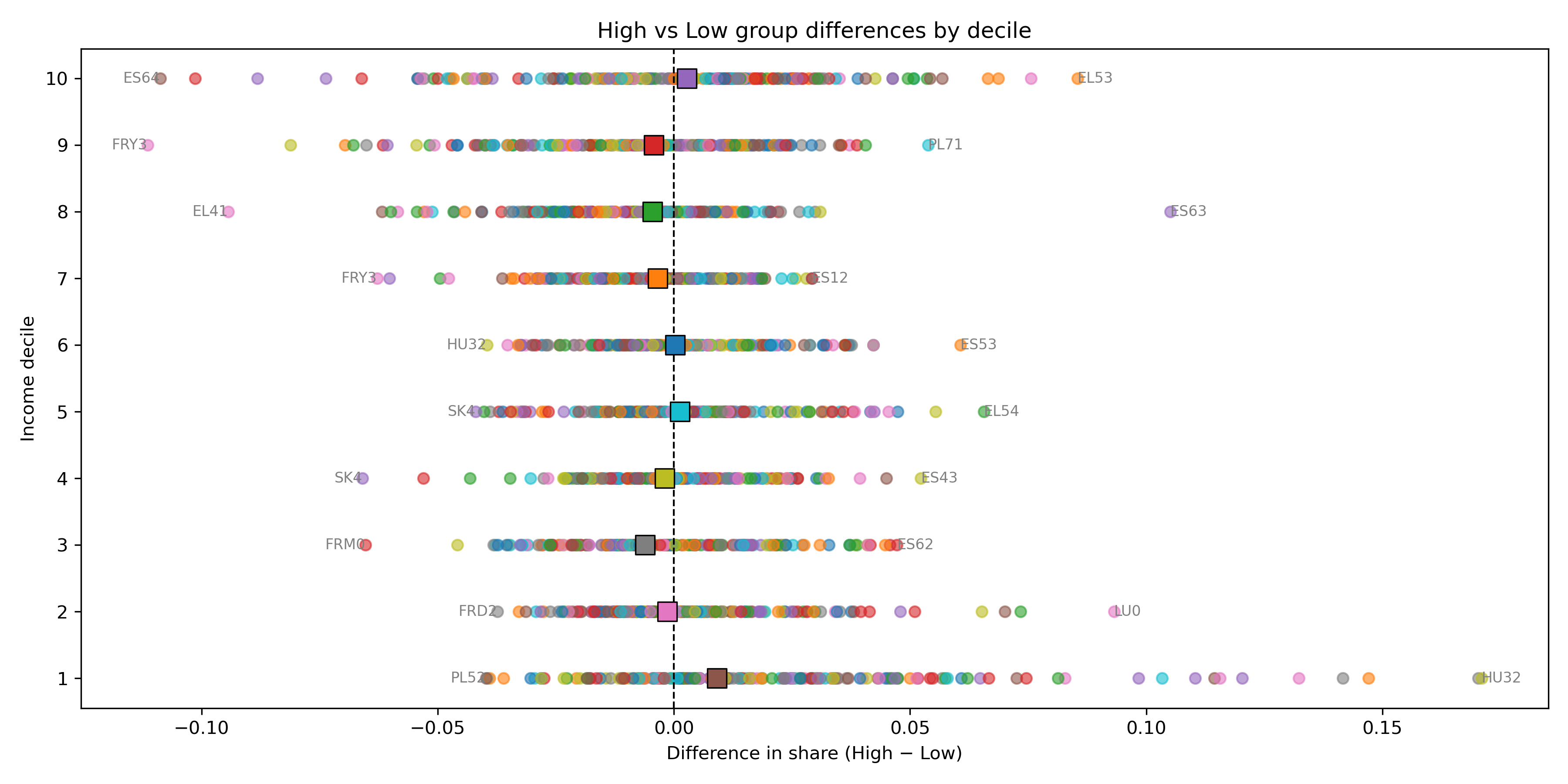

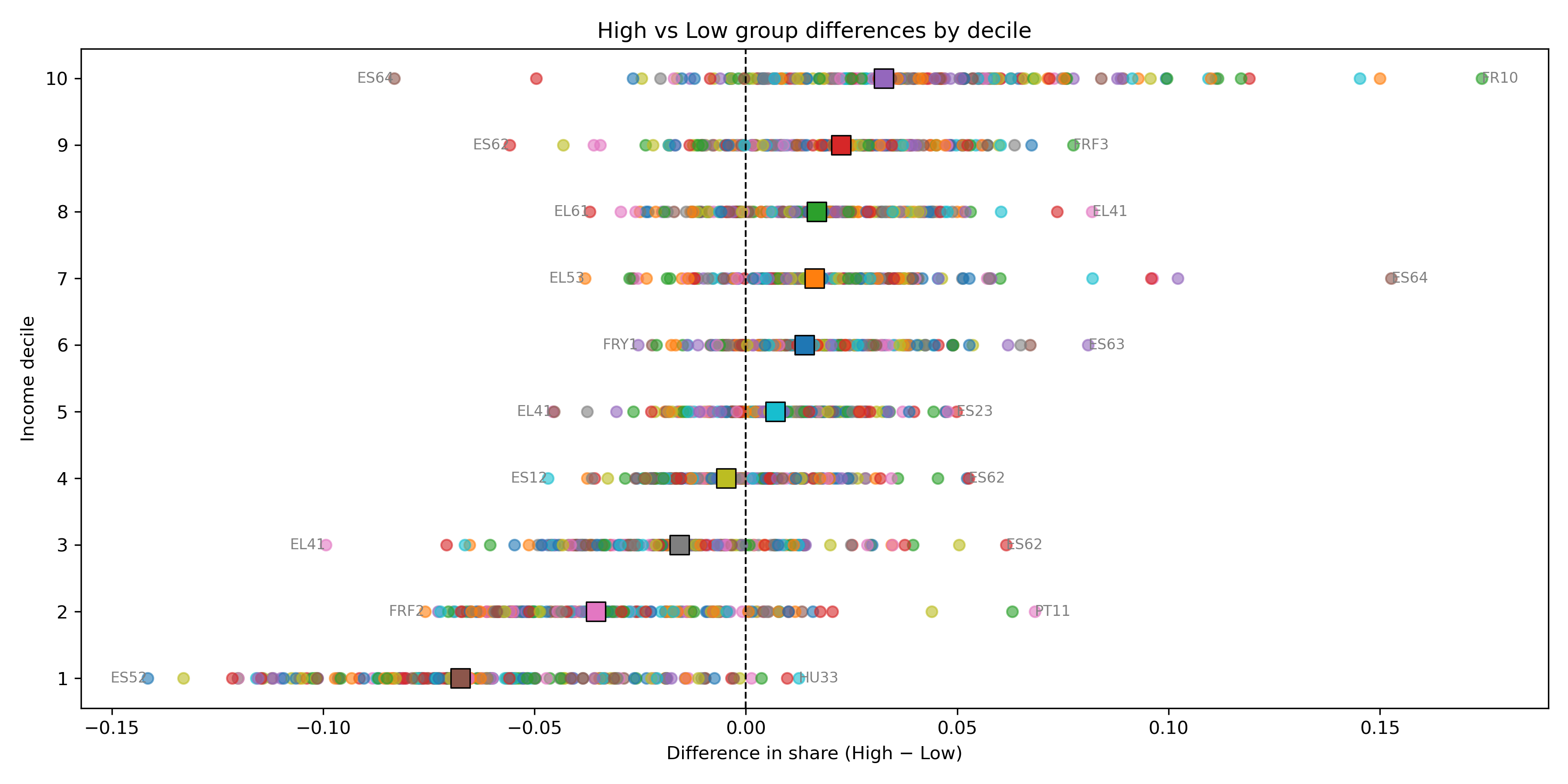

These structural differences have tangible distributional consequences. The following pictures show the distribution of workers across the income ladder according to their exposure to green, digital, and twin occupations. Each of the three figures compares workers in occupations with high exposure to the transition (digital, green, or twin) with those in low-exposure occupations. The vertical axis shows the income deciles, from the lowest (1) to the highest (10). The horizontal axis reports the difference in the share of workers between the two groups within each decile. Positive values mean that workers in high-exposure occupations are more present in that decile; negative values indicate the opposite. Every dot represents a region (NUTS 2), revealing the geographic variation behind the averages, while the larger squares reports the median region for that decile.

The pattern is most pronounced for digital exposure. In the digital figure, high-exposure workers increasingly populate the upper income deciles, with average differences turning positive and growing in magnitude as one moves up the distribution. This confirms that digitalisation is closely associated with higher-quality, better-paid jobs across Europe. At the bottom of the distribution, the opposite pattern emerges: low-exposure workers dominate the lowest deciles, revealing the stratifying effect of digital divides. As for the green exposure figure, we can observe a much more mixed distribution. High-green-exposure workers appear across all income deciles. This dispersion reflects the heterogeneity of green occupations, which range from high-skill technical roles to lower-paid, labour-intensive activities. As a result, green exposure alone does not systematically predict a worker’s position in the income distribution. Finally, the twin exposure figure, capturing occupations requiring both green and digital skills, resembles the digital pattern but is noticeably more fragmented. In several deciles, especially toward the top, high-exposure workers are more prevalent, but the variation across regions is substantial.

Overall, the figures highlight that digital competences consistently align with higher incomes, while green competences do not follow a single distributional logic, and twin competences, though promising, are still emerging and unequally spread. This reinforces the idea that without deliberate policy support, the twin transition risks reproducing or intensifying existing labour-market disparities rather than reducing them. The central policy question is therefore not whether the twin transition will reshape Europe’s labour markets, but whether it will do so in a way that is socially inclusive. The findings suggest that without targeted intervention, the transition may reinforce existing inequalities by channelling its benefits toward those regions, sectors, and workers already better positioned to absorb them. The challenge is to prevent a new divide between transition-ready areas and those left struggling to adapt.

This calls for a renewed commitment to place-sensitive and group-sensitive policy design. Strengthening digital capabilities in lagging regions, ensuring that green sectors offer pathways into stable and well-paid employment, and expanding access to training for women, younger workers, and those in precarious jobs will be essential. Europe must decide whether the twin transition becomes a vector of opportunity or a source of further fragmentation. The evidence makes clear that achieving a just transition will require not only technological progress, but deliberate strategies to broaden access to its benefits.

Distribution of workers across the income ladder according to their exposure to digital transition.

Distribution of workers across the income ladder according to their exposure to green transition.

Distribution of workers across the income ladder according to their exposure to twin transition.

Article prepared by Nicolo Barbieri, University of Ferrara.